JAPANESE

SOCIETY

Chie Nakane

Chapter One: Criteria of Group Formation

1. Attribute and frame

2. Emotional participation and one-to-one relationships

Chapter Two: The Internal Structure of the Group

1. The development of ranking

2. The fundamental structure of vertical organization

3. Qualification of the leader and interpersonal relations in the group

4. The undifferentiated rôle of the group member

Chapter Three: The Overall Structure of the Society

Chapter Four: Characteristics and Value Orientation of Japanese Man

1. From school to employment

2. The web or comradeship

3. Localism and tangibility

This short work presents a configuration of the important elements to be found in contemporary Japanese social life, and attempts to shed new light on Japanese society. I deal with my own society as a social anthropologist using some of the methods which I am accustomed to applying in examining any other society. However, its form is not that of a scientific thesis (as may be seen at once from the absence of a bibliography; I have also refrained from quoting any statistical figures or precise data directly obtained from field surveys).

In this book I have tried to construct a structural image of Japanese society, synthesizing the major distinguishing features to be found in Japanese life. I have drawn evidence almost at random from a number of different types of community to be found in Japan today ― industrial enterprises, government organizations, educational institutions, intellectual groups, religious communities, political parties, village communities, individual households and so on. Throughout my investigation of groups in such varied fields, I have concentrated my analysis on individual behaviour and interpersonal relations which provide the base of both the group organization and the structural tendencies dominating in the development of a group.

It may appear to some that my statements in this book are in some respects exaggerated or over-generalized; such critics might raise objections based on the observations that they themselves happen to have made. Others might object that my examples are not backed by precise or detailed data. Certainly this book does not cover the entire range of social phenomena in Japanese life, nor does it pretend to offer accurate data relevant to a particular community. This is not a description of Japanese society or culture or the Japanese people, nor an explanation of limited phenomena such as the urbanization or modernization of Japan. Rather, it is my intention that this book will offer a key (a source of intelligence and insight) to an understanding of Japanese society, and those features which are specific to it and which distinguish it from other complex societies. I have used wide-ranging suggestive evidence as material to illustrate the crucial aspects of Japanese life, for the understanding of the structural core of Japanese society rather as an artist uses his colours. I had a distinct advantage in handling these colours, for they are colours in which I was born and among which I grew up; I know their delicate shades and effects. In handling these colours, I did not employ any known sociological method and theory. Instead, I have used anything available which seemed to be effective in bringing out the core of the subject matter. This is an approach which might be closer to that of the social anthropologist than to that of the conventional sociologist.

The theoretical basis of the present work was originally established in my earlier study, Kinship and Economic Organization in Rural Japan (Athlone Press, London, 1967). This developed out of my own field work, including detailed monographs by others, in villages in Japan and, as soon as that research was completed, I was greatly tempted to test further, in modern society, the ideas which had emerged from my examination of a rather traditional rural society. In my view, the traditional social structure of a complex society, such as Japan, China or India, seems to persist and endure in spite of great modern changes. Hence, a further and wider exploration of my ideas, as attempted in this book, was called for in order to strengthen the theoretical basis of my earlier study.

Some of the distinguishing aspects of Japanese society which I treat in this book are not exactly new to Japanese and western observers and may be familiar from discussions in previous writings on Japan. However, my interpretations are different and the way in which I synthesize these aspects is new. Most of the sociological studies of contemporary Japan have been concerned primarily with its changing aspects, pointing to the 'traditional' and 'modern' elements as representing different or opposing qualities. The hey-day of this kind of approach came during the American occupation and in the immediately subsequent years, when it was the standpoint adopted by both Japanese and American social scientists. The tendency towards such an approach is still prevalent; it is their thesis that any phenomena which seem peculiar to Japan, not having been found in western society, can be labelled as 'feudal' or 'pre-modern' elements, and are to be regarded as contradictory or obstructive to modernization. Underneath such views, it seems that there lurks a kind of correlative and syllogistic view of social evolution: when it is completely modernized Japanese society will or should become the same as that of the west. The proponents of such views are interested either in uprooting feudal elements or in discovering and noting modern elements which are comparable to those of the west. The fabric of Japanese society has thus been made to appear to be torn into pieces of two kinds. But in fact it remains as one well-integrated entity. In my view, the 'traditional' is one aspect (not element) of the same social body which also has 'modern' features. I am more interested in the truly basic components and their potentiality in the society ― in other words, in social persistence.

The persistence of social structure can be seen clearly in the modes of personal social relation which determine the probable variability of group organization in changing circumstances. This persistence reveals the basic value orientation inherent in society, and is the driving force of the development of society. Social tenacity is dependent largely on the degree of integration and the time span of the history of a society. In Japan, India, China and elsewhere, rich and well-integrated economic and social development occurred during the pre-modern period, comparable to the 'post-feudal' era in European history, and helped create a unique institutionalization of social ideals. Values that crystallized into definite form during the course of pre-modern history are deeply rooted and aid or hinder, as the case may be, the process of modernization. To explore these values in terms of their effects on social structure appears to me to be a fascinating subject for the social sciences. In this light, I think Japan presents a rich field for the development of a theory of social structure. I approach this issue through a structural analysis, not a cultural or historical explanation. The working of what I call the vertical principle in Japanese society is the theme of this book. In my view, the most characteristic feature of Japanese social organization arises from the single bond in social relationships: an individual or a group has always one single distinctive relation to the other. The working of this kind of relationship meets the unique structure of Japanese society as a whole, which contrasts to that of caste or class societies. Thus Japanese values are manifested. Some of my Japanese readers might feel repelled in the face of some parts of my discussion; where I expose certain Japanese weaknesses they might even feel considerable distaste. I do this, however, not because of a hypercritical view of the Japanese or Japanese life but because I intend to be as objective as possible in this analysis of the society to which I belong. I myself take these weaknesses for granted as elements which constitute part of the entire body which also has its great strengths.

Finally, I wish to express my profound thanks to Professor Ernest Gellner, whose very stimulating and detailed comments as editor helped me a great deal in completing the final version of the manuscript. I am greatly indebted to Professor Geoffrey Bownas, who kindly undertook the difficult task of correcting my English. I was fascinated by the way he found it possible to make my manuscript so much more readable without altering even a minor point in the flow of my discussion.

C.N.

Chapter

One:

Criteria of Group Formation

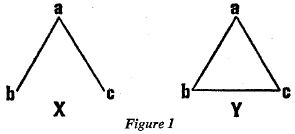

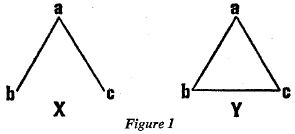

The following analysis employs two basic but contrasting criteria. These are attribute and frame, concepts newly formulated here, but which, I think, are illuminating and useful in a comparative study of Japanese and other societies.

It is important, however, to redefine our terms. In this analysis groups may be identified by applying the two criteria: one is based on the individual's common attribute, the other on situational position in a given frame. I use frame as a technical term with a particular significance as opposed to the criterion of attribute, which, again, is used specifically and in a broader sense than it normally carries. Frame may be a locality, an institution or a particular relationship which binds a set of individuals into one group: in all cases it indicates a criterion which sets a boundary and gives a common basis to a set of individuals who are located or involved in it. In fact, my term frame is the English translation of the Japanese ba, the concept from which I originally evolved my theory, but for which it is hard to find the exact English counterpart. Ba means 'location', but the normal usage of the term connotes a special base on which something is placed according to a given purpose. The term ba is also used in physics for 'field' in English.

Let me indicate how these two technical terms can be applied to various actual contexts. Attribute may mean, for instance, being a member of a definite descent group or caste, In contrast, being a member of X village expresses the commonality of frame. Attribute may be acquired not only by birth but by achievement. Frame is more circumstantial. These criteria serve to identify the individuals in a certain group, which can then in its turn be classified within the whole society, even though the group may of may not have a particular function of its own as a collective body. Classifications such as landlord and tenant are based on attribute, while such a unit as a landlord and his tenants is a group formed by situational position. Taking industry as an example, 'lathe operator' or 'executive' refers to attribute, but 'members of Y Company' refers to frame. In the same way, 'professor', 'office clerk' and 'student' are attributes, whereas 'men of Z University' is a frame.

In any society, individuals are gathered into social groups or social strata on the bases of attributes and frame. There may be some cases where the two factors coincide in the formation of a group, but usually they overlap each other, with individuals belonging to different groups at the same time. The primary concern in this discussion is the relative degree of function of each criterion. There are some cases where either the attribute or the frame factor functions alone, and some where the two are mutually competitive. The way in which the factors are commonly weighted bears a close reciprocal relationship to the values which develop in the social consciousness of the people in the society. For example, the group consciousness of the Japanese depends considerably on this immediate social context, frame, whereas in India it lies in attribute (most symbolically expressed in caste, which is fundamentally a social group based on the ideology of occupation and kinship). On this point, perhaps, the societies of Japan and India show the sharpest contrast, as will be discussed later in greater detail.

The ready tendency of the Japanese to stress situational position in a particular frame, rather than universal attribute, can be seen in the following example: when a Japanese 'faces the outside' (confronts another person) and affixes some position to himself socially he is inclined to give precedence to institution over kind of occupation. Rather than saying, 'I am a typesetter' or 'I am a filing clerk', he is likely to say, 'I am from B the Publishing Group' or 'I belong to S Company'. Much depends on context, of course, but where a choice exists, he will use this latter form. (I will discuss later the more significant implications for Japanese social life indicated by this preference.) The listener would rather hear first about the connection with B Publishing Group or S Company; that he is a journalist or printer, engineer or office worker is of secondary importance. When a man says he is from X Television one may imagine him to be a producer or cameraman, though he may in fact be a chauffeur. (The universal business suit makes it hard to judge by appearances.) In group identification, a frame such as a 'company' or 'association' is of primary importance; the attribute of the individual is a secondary matter. The same tendency is to be found among intellectuals: among university graduates, what matters most, and functions the strongest socially, is not whether a man holds or does not hold a PhD but rather from which university he graduated. Thus the criterion by which Japanese classify individuals socially tends to be that of particular institution, rather than of universal attribute. Such group consciousness and orientation fosters the strength of an institution, and the institutional unit (such as school or company) is in fact the basis of Japanese social organization, as will be discussed extensively in Chapter Three. The manner in which this group consciousness works is also revealed in the way the Japanese uses the expression uchi (my house) to mean the place of work, organization, office or school to which he belongs; and otaku (your house) to mean a second person's place of work and so on. The term kaisha symbolizes the expression of group consciousness. Kaisha does not mean that individuals are bound by contractual relationships into a corporate enterprise, while still thinking of themselves as separate entities; rather, kaisha is 'my' or 'our' company, the community to which one belongs primarily, and which is all-important in one's life. Thus in most cases the company provides the whole social existence of a person, and has authority over all aspects of his life; he is deeply emotionally involved in the association.[1] That Company A belongs not to its shareholders, but rather belongs to 'us', is the sort of reasoning involved here, which is carried to such a point that even the modern legal process must compromise in face of this strong native orientation. I would not wish to deny that in other societies an employee may have a kind of emotional attachment to the company or his employer; what distinguishes this relation in Japan is the exceedingly high degree of this emotional involvement. It is openly and frequently expressed in speech and behaviour in public as well as in private, and such expressions always receive social and moral appreciation and approbation.

The essence of this firmly rooted, latent group consciousness in Japanese society is expressed in the traditional and ubiquitous concept of ie, the household, a concept which penetrates every nook and cranny of Japanese society. The Japanese usage uchi-no referring to one's work place indeed derives from the basic concept of ie. The term ie also has implications beyond those to be found in the English words 'household' or 'family'.

The concept of ie, in the guise of the term 'family system', has been the subject of lengthy dispute and discussion by Japanese legal scholars and sociologists. The general consensus is that, as a consequence of modernization, particularly because of the new post-war civil code, the ie institution is dying. In this ideological approach the ie is regarded as being linked particularly with feudal moral precepts; its use as a fundamental unit of social structure has not been fully explored.

In my view, the most basic element of the ie institution is not that form whereby the eldest son and his wife live together with the old parents, nor an authority-structure in which the household head holds the power and so on. Rather, the ie is a corporate residential group and, in the case of agriculture or other similar enterprises, ie is a managing body. The ie comprises household members (in most cases the family members of the household head, but others in addition to family members may be included), who thus make up the units of a distinguishable social group. In other words, the ie is a social group constructed on the basis of an established frame of residence and often of management organization. What is important here is that the human relationships within this household group are thought of as more important than all other human relationships. Thus the wife and daughter-in-law who have come from outside have incomparably greater importance than one's own sisters and daughters, who have married and gone into other households. A brother, when he has built a separate house, is thought of as belonging to another unit or household; on the other hand, the son-in-law, who was once a complete outsider, takes the position of a household member and becomes more important than the brother living in another household. This is remarkably different from societies such as that of India, where the weighty factor of sibling relationship (a relationship based on commonality of attribute, that of being born of the same parents) continues paramount until death, regardless of residential circumstances; theoretically, the stronger the factor of sibling relationship, the weaker the social independence of a household as a residence unit (It goes without saying, of course, that customs such as the adopted son-in-law system prevalent in Japan are non-existent in Hindu society. The same is true of Europe.) These facts support the theory that group-forming criteria based on functioning by attribute oppose group-forming criteria based on functioning by frame.

Naturally, the function of forming groups on the basis of the element of the frame, as demonstrated in the formation of the household, involves the possibility of including members with a differing attribute, and at the same time expelling a member who has the same attribute. This is a regular occurrence, particularly among traditional agricultural and merchant households. Not only may outsiders with not the remotest kinship tie be invited to be heirs and successors but servants and clerks are usually incorporated as members of the household and treated as family members by the head of the household. This inclusion must be accepted without reservation to ensure that when a clerk is married to the daughter of the household and becomes an adopted son-in-law the household succession will continue without disruption.

Such a principle contributes to the weakening of kinship ties. Kinship, the core of which lies in the sibling relation, is a criterion based on attribute. Japan gives less weight to kinship than do other societies, even England; in fact, the function of kinship is comparatively weak outside the household. The saying 'the sibling is the beginning of the stranger' accurately reflects Japanese ideas on kinship. A married sibling who lives in another household is considered a kind of outsider. Towards such kin, duties and obligations are limited to the level of the seasonal exchange of greetings and presents, attendance at wedding and funeral ceremonies and the minimum help in case of accident or poverty. There are often instances where siblings differ widely in social and economic status; the elder brother may be the mayor, while his younger brother is a postman in the same city; or a brother might be a lawyer or businessman, while his widowed sister works as a domestic servant in another household. The wealthy brother normally does not help the poor brother or sister, who has set up a separate household, as long as the latter can somehow support his or her existence; by the same token, the latter will not dare to ask for help until the last grain of rice has gone. Society takes this for granted, for it gives prime importance to the individual household rather than to the kin group as a whole.

This is indeed radically different from the attitude to kin found in India and other south east Asian countries, where individual wealth tends to be distributed among relatives; here the kin group as a whole takes precedence over the individual household and nepotism plays an important role. I have been surprised to discover that even in England and America, brothers and sisters meet much more frequently than is required by Japanese standards, and that there exists such a high degree of attachment to kinfolk. Christmas is one of the great occasions when these kinfolk gather together; New Year's Day is Japan's equivalent to the western Christmas, everyone busy with preparations for visits from subordinate staff, and then, in turn, calling on superiors. There is little time and scope to spare for collateral kin ― married brothers, sisters, cousins, uncles and aunts and so on ― though parents and grandparents will certainly be visited if they do not live in the same house. Even in rural areas, people say 'One's neighbour is of more importance than one's relatives' or 'You can carry on your life without cousins, but not without your neighbours'.

The kinship which is normally regarded as the primary and basic human attachment seems to be compensated in Japan by a personalized relation to a corporate group based on work, in which the major aspects of social and economic life are involved. Here again we meet the vitally important unit in Japanese society of the corporate group based on frame. In my view, this is the basic principle on which Japanese society is built.

To sum up, the principles of Japanese social group structure can be seen clearly portrayed in the household structure. The concept of this traditional household institution, ie, still persists in the various group identities which are termed uchi, a colloquial form of ie. These facts demonstrate that the formation of social groups on the basis of fixed frames remains characteristic of Japanese social structure.

Among groups larger than the household, there is that described by the medieval concept, ichizoku-rōtō (one family group and its retainers). The idea of group structure as revealed in this expression is an excellent example of the frame-based social group. This is indeed the concept of one household, in which family members and retainers are not separated but form an integrated corporate group. There are often marriage ties between the two sides of this corporate group, and all lines of distinction between them become blurred. The relationship is the same as that between family members and clerks or servants in a household. This is a theoretical antithesis to a group formed exclusively on lineage or kin.

The equivalent in modern society of ie and ichizoku-rōtō is a group such as 'One Railway Family' (kokutetsu-ikka), which signifies the Japanese National Railways. A union, incorporating both workers and management, calls this 'management-labour harmony'. Though it is often said that the traditional family (ie) institution has disappeared, the concept of the ie still persists in modern contexts. A company is conceived as an ie, all its employees qualifying as members of the household, with the employer at its head. Again this 'family' envelops the employee's personal family; it 'engages' him 'totally' (marugakae in Japanese). The employer readily takes responsibility for his employee's family, for which, in turn, the primary concern is the company, rather than relatives who reside elsewhere. (The features relating the company with its employees' families will be discussed later, pp. 14-15.) In this modern context, the employee's family, which normally comprises the employee himself, his wife and children, is a unit which can no longer be conceived as an ie, but simply a family. The unit is comparable to the family of a servant or clerk who worked in the master's ie, the managing body of the pre-modern enterprise. The role of the ie institution as the distinct unit in society in pre-modern times is now played by the company. This social group consciousness symbolized in the concept of the ie, of being one unit within a frame, has been achievable at any time, has been promoted by slogans and justified in the traditional morality.

This analysis calls for a reconsideration of the stereotyped view that modernization or urbanization weakens kinship ties, and creates a new type of social organization on entirely different bases. Certainly industrialization produces a new type of organization, the formal structure of which may be closely akin to that found in modern western societies. However, this does not necessarily accord with changes in the informal structure, in which, as in the case of Japan, the traditional structure persists in large measure. This demonstrates that the basic social structure continues in spite of great changes in social organization.[2]

2. Emotional participation and one-to-one-relationships

It is clear from the previous section that social groups constructed with particular reference to situation, i.e. frame, include members with differing attributes. A group formed on the basis of commonality of attribute can possess a strong sense of exclusiveness, based on this homogeneity, even without recourse to any form of law. Naturally, the relative strength of this factor depends on a variety of conditional circumstances, but in the fundamentals of group formation this homogeneity among group members stands largely by its own strength, and conditions are secondary. When a group develops on the situational basis of frame the primary form is a simple herd which in itself does not possess internal positive elements which can constitute a social group. Constituent elements of the group in terms of their attributes may be heterogenous but may not be complementary. (The discussion here does not link with Durkheimian Theory as such; the distinction is between societies where people stick together because they are similar and those where they stick together because they are complementary.) For example, a group of houses built in the same area may form a village simply by virtue of physical demarcation from other houses. But in order to create a functional corporate group, there is need of an internal organization which will link these independent households. In such a situation some sort of law must be evolved to guide group coherence.

In addition to the initial requirement of a strong, enduring frame, there is need to strengthen the frame even further and to make the group element tougher. Theoretically, this can be done in two ways. One is to influence the members within the frame in such a way that they have a feeling of 'one-ness'; the second method is to create an internal organization which will tie the individuals in the group to each other and then to strengthen this organization. In practice, both these modes occur together, are bound together and progress together; they become, in fact, one common rule of action, but for the sake of convenience I shall discuss them separately. In this section I discuss the feeling of unity; in the following chapter I shall consider internal organization.

People with different attributes can be led to feel that they are members of the same group, and that this feeling is justified, by stressing the group consciousness of 'us' against 'them', i.e. the external, and by fostering a feeling of rivalry against other similar groups. In this way there develops internally the sentimental tie of 'members of the same troop'.

Since disparity of attribute is a rational thing, an emotional approach is used to overcome it. This emotional approach is facilitated by continual human contact of the kind that can often intrude on those human relations which belong to the completely private and personal sphere. Consequently, the power and influence of the group not only affects and enters into the individual's actions; it alters even his ideas and ways of thinking. Individual autonomy is minimized. When this happens, the point where group or public life ends and where private life begins no longer can be distinguished. There are those who perceive this as a danger, an encroachment on their dignity as individuals; on the other hand, others feel safer in total group-consciousness. There seems little doubt that the latter group is in the majority. Their sphere of living is usually concentrated solely within the village community or the place of work. The Japanese regularly talk about their homes and love affairs with co-workers; marriage within the village community or place of work is prevalent; the family frequently participates in company pleasure trips. The provision of company housing, a regular practice among Japan's leading enterprises, is a good case in point. Such company houses are usually concentrated in a single area and form a distinct entity within, say, a suburb of a large city. In such circumstances employees' wives come into close contact with and are well informed about their husbands' activities. Thus, even in terms of physical arrangements, a company with its employees and their families forms a distinct social group. In an extreme case, a company may have a common grave for its employees, similar to the household grave. With group-consciousness so highly developed there is almost no social life outside the particular group on which an individual's major economic life depends. The individual's every problem must be solved within this frame. Thus group participation is simple and unitary. It follows then that each group or institution developes a high degree of independence and closeness, with its own internal law which is totally binding on members.

The archetype of this kind of group is the Japanese 'household' (ie) as we have described it in the previous section. In Japan, for example, the mother-in-law and daugther-in-law problem is preferably solved inside the household, and the luckless bride has to struggle through in isolation, without help from her own family, relatives or neighbours. By comparison, in agricultural villages in India not only can the bride make long visits to her parental home but her brother may frequently visit her and help out in various ways. Mother-in-law and daughter-in-law quarrels are conducted in raised voices that can be heard all over the neighbourhood, and when such shouting is heard all the women (of the same caste) in the neighbourhood come over to help out. The mutual assistance among the wives who come from other villages is a quite enviable factor completely unimaginable among Japanese women. Here again the function of the social factor of attribute (wife) is demonstrated; it supersedes the function of the frame of the household. In Japan, by contrast, 'the parents step in when their children quarrel' and, as I shall explain in detail later, the structure is the complete opposite to that in India.

Moral ideas such as 'the husband leads and the wife obeys' or 'man and wife are one flesh' embody the Japanese emphasis on integration. Among Indians, however, I have often observed husband and wife expressing quite contradictory opinions without the slightest hesitation. This is indeed rare in front of others in Japan. The traditional authority of the Japanese household head, once regarded as the prime characteristic of the family system, extended over the conduct, ideas and ways of thought of the household's members, and on this score the household head could be said to wield a far greater power than his Indian counterpart. In Indian family life there are all kinds of rules that apply in accordance with the status of the individual family member: the wife, for instance, must not speak directly to her husband's elder brothers, father, etc. These rules all relate to individual behaviour, but in the sphere of ideas and ways of thought the freedom and strong individuality permitted even among members of the same family is surprising to a Japanese. The rules, moreover, do not differ from household to household, but are common to the whole community, and especially among the members of the same caste community. In other words, the rules are of universal character, rather than being situational or particular to each household, as is the case in Japan.[3] Compared with traditional Japanese family life, the extent to which members of an Indian household are bound by the individual household's traditional practices is very small.

An Indian who had been studying in Japan for many years once compared Japanese and Indian practice in the following terms:

Why does a Japanese have to consult his companions over even the most trivial matter? The Japanese always call a conference about the slightest thing, and hold frequent meetings, though these are mostly informal, to decide everything. In India, we have definite rules as family members (and this is also true of other social groups), so that when one wants to do something one knows whether it is all right by instantaneous reflection on those rules ― it is not necessary to consult with the head or with other members of the family. Outside these rules, you are largely free to act as an individual; whatever you do, you have only to ask whether or not it will run counter to the rules.

As this clearly shows, in India 'rules' are regarded as a definite but abstract social form, not as a concrete and individualized form particular to each family/social group as is the case in Japan. The individuality of the Indian family unit is not strong, nor is there group participation by family members of the order of the emotional participation in the Japanese household; nor is the family as a living unit (or as a group holding communal property) a closed community as in the case of the Japanese household. Again, in contrast to Japanese practice, the individual in India is strongly tied to the social network outside his household.

In contrast to the Japanese system, the Indian system allows freedom in respect of ideas and ways of thought as opposed to conduct. I believe for this reason, even though there are economic and ethical restrictions on the modernization of society, the Indian does not see his traditional family system as an enemy of progress to such a degree as the Japanese does. This view may contradict that conventionally held by many people on the Indian family. It is important to note that the comparison here is made between Japanese and Hindu systems focused on actual interpersonal relationships within the family or household, rather than between western and Indian family patterns in a general outlook. I do not intend here to present the structure and workings of actual personal relations in Japanese and Hindu families in detail, but the following point would be of some help in indicating my thesis. In the ideal traditional household in Japan, for example, opinions of the members of the household should always be held unanimously regardless of the issue, and this normally meant that all members accepted the opinion of the household head, without even discussing the issue. An expression of a contradictory opinion to that of the head was considered a sign of misbehavior, disturbing the harmony of the group order. Contrasted to such a unilateral process of decision making in the Japanese household, the Indian counterpart allows much room for discussion between its members; they, whether sons, wife or even daughters, are able to express their views much more freely and they in fact can enjoy a discussion, although the final decision may be taken by the head. Hindu family structure is similar hierarchically to the Japanese family, but the individual's rights are well preserved in it. In the Japanese system all members of the household are in one group under the head, with no specific rights according to the status of individuals within the family. The Japanese family system differs from that of the Chinese system, where family ethics are always based on relationships between particular individuals such as father and son, brothers and sisters, parent and child, husband and wife, while in Japan they are always based on the collective group, i.e. members of a household, not on the relationships between individuals.

The Japanese system naturally produces much more frustration in the members of lower status in the hierarchy; and allows the head to abuse the group or an individual member. In Japan, especially immediately after the second world war, the idea has gained ground that the family system (ie) was an evil, feudalistic growth obstructing modernization, and on this premise one could point out the evil uses to which the unlimited infiltration of the household head's authority were put. It should be noticed here, however, that although the power of each individual household head is often regarded as exclusively his own, in fact it is the social group, the 'household', which has the ultimate integrating power, a power which restricts each member's behaviour and thought, including that of the household head himself.

Another group characteristic portrayed in the Japanese household can be seen when a business enterprise is viewed as a social group. In this instance a closed social group has been organized on the basis of the 'life-time employment system' and the work made central to the employees' lives. The new employee is in just about the same position and is, in fact, received by the company in much the same spirit as if he were a newly born family member, a newly adopted son-in-law or a bride come into the husband's household. A number of well-known features peculiar to the Japanese employment system illustrate this characteristic, for example, company housing, hospital benefits, family recreation groups for employees, monetary gifts from the company on the occasion of marriage, birth or death and even advice from the company's consultant on family planning. What is interesting here is that this tendency is very obvious even in the most forward-looking, large enterprises or in supposedly modern, advanced management. The concept is even more evident in Japan's basic payment system, used by every industrial enterprise and government organization,in which the family allowance is the essential element. This is also echoed in the principle of the seniority payment system.

The relationship between employer and employee is not to be explained in contractual terms. The attitude of the employer is expressed by the spirit of the common saying, 'the enterprise is the people'. This affirms the belief that employer and employee are bound as one by fate in conditions which produce a tie between man and man often as firm and close as that between husband and wife. Such a relationship is manifiestly not a purely contractual one between employer and employee; the employee is already a member of his own family, and all members of his family are naturally included in the larger company 'family'. Employers do not employ only a man's labour itself but really employ the total man, as is shown in the expression marugakae (completely enveloped). This trend can be traced consistently in Japanese management from the Meiji period to the present.

The life-time employment system, characterized by the integral and lasting commitment between employee and employer, contrasts sharply with the high mobility of the worker in the United States. It has been suggested that this system develops from Japan's economic situation and is closely related to the surplus of labour. However, as J. C. Abegglen has suggested in his penetrating analysis,[4] the immobility of Japanese labour is not merely an economic problem. That it is also closely related to the nature of Japanese social structure will become evident from my discussion. In fact, Japanese labour relations in terms of surplus and shortage of labour have least affected the life-time employment system. Indeed, these contradictory situations have together contributed to the development of the system.

It might be appropriate at this point to give a brief description of the history of the development of the life-time employment system in Japan. In the early days of Japan's industrialization, there was a fairly high rate of movement of factory workers from company to company, just as some specific type of workmen or artisans of pre-industrial urban Japan had moved freely from job to job. Such mobility in some workers in pre-industrial and early industrial Japan seems to be attributed to the following reasons: a specific type of an occupation, the members of which consisted of a rather small percentage of the total working population and the demand for them was considerably high; these workers were located in a situation outside well established institutionalized systems. The mobility of factory workers caused uncertainty and inconvenience to employers in their efforts to retain a constant labour force. To counteract this fluidity, management policy gradually moved in the direction of keeping workers in the company for their entire working lives, rather than towards developing a system based on contractual arrangements. By the beginning of this century larger enterprises were already starting to develop management policies based on this principle; they took the form of various welfare benefits, company houses at nominal rent, commissary purchasing facilities and the like. This trend became particularly marked after the first world war when the shortage of labour was acute.

It was also at the end of the first world war that there came into practice among large companies the regular employment system by which a company takes on each spring a considerable number of boys who have just left school. This development arose from the demand for company-trained personnel adapted to the mechanized production systems that followed the introduction of new types of machinery from Germany and the United States. Boys fresh from school were the best potential labour force for mechanized industy because they were more easily moulded to suit a company's requirements. They were trained by the company not only technically but also morally. In Japan it has always been believed that individual moral and mental attitudes have an important bearing on productive power. Loyalty towards the company has been highly regarded. A man may be an excellent technician, but if his way of thought and his moral attitudes do not accord with the company's ideal the company does not hesitate to dismiss him. Men who move in from another company at a comparatively advanced stage in their working life tend to be considered difficult to mould or suspect in their loyalties. Ease of training, then, was the major reason why recruitment of workers was directed more and more towards boys fresh from school.[5]

Recruitment methods thus paved the way for the development of the life-employment system. An additional device was evolved to hold workers to a company, for example, the seniority payment system based on duration of service, age and educational qualifications, with the added lure of a handsome payment on retirement. The principle behind this seniority system had the advantage of being closely akin to the traditional pattern of commercial and agricultural mangement in pre-industrial Japan. In these old-style enterprises operational size had been relatively small ― one household or a group of affiliated households centred on one particular household, the head of which acted as employer while his family members and affiliated members or servants acted as permanent employees. Thus the pattern of employment in a modern industrial enterprise has close structural and ideological links with traditional household management.

The shift towards life-employment was assisted in the second and third decades of this century by developments in the bureaucratic structure of business enterprises: a proliferation of sections was accompanied by finer gradings in official rank. During these twenty years there appeared uniforms for workers, badges (lapel buttons) worn as company insignia and stripes on the uniform cap to indicate section and rank. Workers thus came under a more rigid institutional hierarchy, but they were also given greater incentives by the expectation of climbing the delicately subdivided ladder of rank.

During the war this system was strengthened further by the adoption of a military pattern. Labour immobility was reinforced by government policy, which cut short the trend to increased mobility that had been the result of the acute shortage of labour. The prohibition on movement of labour between factories was bolstered by the moral argument that it was through concentrated service to his own factory that a worker could best serve the nation. The factory was to be considered as a household or family, in which the employer would and should care for both the material and mental life of his worker and the latter's family. According to the 'Draft of Labour Regulations' (Munitions Public Welfare Ministry Publication, February 1945):

The factory, by its production, becomes the arena for putting into practice the true aims of Imperial labour. The people who preserve these aims become the unifiers of labour. Superior and inferior should help each other, those who are of the same rank should co-operate and, with a fellowship as of one family, we shall combine labour and management.

Thus the factory's household-like function came about, in part, at the behest of state authority. In this context, a moral and patriotic attitude was regarded as more important than technical proficiency. Against shortages in the commodity market, the factory undertook to supply rice, vegetables, clothing, lodging accommodation, medical care, etc.

Familialism, welfare services and extra payments supplied by the company were thus fully developed under the peculiar circumstances of war, and have been retained as the institutional pattern in the post-war years. It is also to be noted that the process was further encouraged by post-war union activity. Unions mushroomed after the war, when 48,OOO unions enrolled 9,OOO,OOO members. These unions were formed primarily within a single company and encompassed members of different types of occupation and qualification, both staff and line workers. It is said that, in some aspects, a union is like the wartime Industrial Patriotism Club (Sangyō-hōkoku-kai), lacking only the company president. Thus it can serve as part of the basis of familialism. The establishment of welfare facilities, company housing schemes, recreation centres at seaside or hill resorts, etc., are all items demanded by the unions along with wage increases. Above all, the single most important union success was the gaining of the right of appeal against summary dismissal or lay-off. In the period immediately after the war dismissal meant starvation; this, together with the swiftly increasing power of the union movement, accounts for the unions' success in acquiring this tremendous privilege. Thus life employment, a policy initiated by management, has reached its perfected form through the effect of post-war unionism. Again, to combat the shortage of younger workers and highly trained engineers which is felt so acutely today, management policy is moving further towards attempts at retaining labour by the offer of more beneficial provisions.

As it has shown in the course of its development, life-time employment has advantages for both employer and employee. For the employer it serves to retain the services of skilled workers against times of labour shortage. For the employee it gives security against surplus labour conditions; whatever the market circumstances, there is little likelihood of the employee finding better employment if he once leaves his job. This system has, in fact, been encouraged by contradictory situations ― shortage and surplus of labour. Here is demonstrated a radical divergence between Japan and America in management employment policy; a Japanese employer buys future potential labour and an American employer buys labour immediately required. According to the Japanese reasoning, any deficiencies in the current labour force will be compensated by the development of maximum power in the labour force of the future; the employer buys his labour material and shapes it until it best fits his production need. In America management buys ready-made labour.

Familialism, another offspring of the operational mechanism of modern industrial enterprise, is the twin to life employment. Attention has already been drawn (see p. 7) to the concept of 'The One Railway Family' which was advocated as early as 1909 by then then president of the National Railways, Gotō Shinpei. The concept was strengthened during the war years, and it has appeared in such favourite slogans of post-war management as 'the spirit of love for the company' and 'the new familialism'. According to so-called modern and advanced management theory, a genuinely inspired 'spirit of love for the company' is not merely advocated, but is indeed an atmosphere resulting from management policy, so that 'whether the feeling of love for the company thrives of not is the barometer of the abilities and talents of management staff'. Even in the coining of expressions which may seem antithetical ― 'we must love our company' and 'the spirit of love for the company is silly' ― the underlying motivation remains the securing of the employee's total emotional participation.

In summary, the characteristics of Japanese enterprise as a social group are, first, that the group is itself family-like and, second, that it pervades even the private lives of its employees, for each family joins extensively in the enterprise. These characteristics have been cautiously encouraged by managers and administrators consistently from the Meiji period. And the truth is that this encouragement has always succeeded and reaped rewards.

A cohesive sense of group unity, as demonstrated in the operational mechanism of household and enterprise, is essential as the foundation of the individual's total emotional participation in the group; it helps to build a closed world and results in strong group independence or isolation. This inevitably breeds household customs and company traditions. These in turn are emphasized in mottoes which bolster the sense of unity and group solidarity, and strengthen the group even more. At the same time, the independence of the group and the stability of the frame, both cultivated by this sense of unity, create a gulf between the group and others with similar attributes but outside the frame; meanwhile, the distance between people with differing attributes within the frame is narrowed and the functioning of any group formed on the base of similar attributes is paralysed. Employees in an enterprise must remain in the group, whether they like it or not: not only do they not want to change to another company; even if they desire a change, they lack the means to accomplish it. Because there is no tie between workers of the same kind, as in a 'horizontal' craft union, they get neither information nor assistance from their counterparts. (This situation is identical with that of the Japanese married-in bride as described above.) Thus, in this type of social organization, as society grows more stable, the consciousness of similar qualities becomes weaker and, conversely, the consciousness of the difference between 'our people' and 'outsiders' is sharpened.

The consciousness of 'them' and 'us' is strengthened and aggravated to the point that extreme contrasts in human relations can develop in the same society, and anyone outside 'our' people ceases to be considered human. Ridiculous situations occur, such as that of the man who will shove a stranger out of the way to take an empty seat, but will then, no matter how tired he is, give up the seat to someone he knows, particularly if that someone is a superior in his company.

An extreme example of this attitude in group behaviour is the Japanese people's amazing coldness (which is not a matter just of indifference, but rather of active hostility), the contempt and neglect they will show for the people of an outlying island, or for those living in the 'special' buraku (formerly a segregated social group now legally equal but still discriminated against). Here the complete estrangement of people outside 'our' world is institutionalized. In India there is a lower-class group known as 'untouchables', but although at first glance the Indian attitude towards a different caste appears to resemble Japanese behaviour, it is not really so. The Indian does not have the sharp distinction of 'them' and 'us' between two different groups. Among the various Indian groups, A, B, C, etc., one man happens to belong to A, while another is of B; A, B, C, and so forth together form one society. His group A constitutes part of the whole, while, to the Japanese, 'our' is opposed to the whole world. The Indian's attitude towards people of other groups stems from indifference rather than hostility.

These characteristics of group formation reveal that Japanese group affiliations and human relations are exclusively one-to-one: a single loyalty stands uppermost and firm. There are many cases of membership of more than one group, of course, but in these cases there is always one group that is clearly preferred while the others are considered secondary. By contrast, the Chinese, for example, find it impossible to decide which group is the most important of several. So long as the groups differ in nature, the Chinese see no contradiction and think it perfectly natural to belong to several groups at once. But a Japanese would say of such a case, 'That man is sticking his nose into something else,' and this saying carries with it moral censure. The fact that Japanese pride themselves on this viewpoint and call it fastidiousness is once again very Japanese. The saying 'No man can serve two masters' is wholeheartedly subscribed to by the Japanese. In body-and-soul emotional participation there is no room for serving two masters. Thus, an individual or a group has always one single distinctive relation to the other. This kind of ideal is also manifested in the relationship between the master and his disciple, including the teacher and student today. For a Japanese scholar, the person he calls his teacher (master) is always one particular senior scholar, and he is recognized as belonging linearly to the latter. For him to approach another scholar in competition with his teacher is felt as a betrayal of his teacher, and is particularly unbearable for his teacher. In contrast, for the Chinese it is the traditional norm to have several teachers in one's life and one can learn freely from all of them in spite of the fact that they are in competition.

Thus, in Japanese society not only is the individual's group affiliation one-to-one but, in addition, the ties binding individuals together are also one-to-one. This characteristic single bond in social relationships is basic to the ideals of the various groups within the whole society. The ways in which interpersonal relations reflect this one-to-one linkage will be discussed at length in the next chapter.

Chapter

Two:

The Internal Structure of the Group

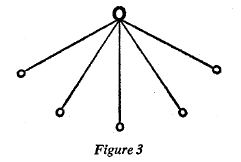

In the foregoing discussion it has been shown that a group where membership is based on the situational position of individuals within a common frame tends to become a closed world. Inside it, a sense of unity is promoted by means of the members' total emotional participation, which further strengthens group solidarity. In general, such groups share a common structure, an internal organization by which the members are tied vertically into a delicately graded order.

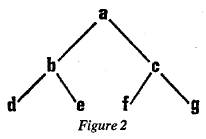

Before I outline my analysis of this structure of internal organization I propose a set of effective concepts as the analytical basis of the following discussion. In abstract terms, the essential types of human relations can be divided, according to the ways in which ties are organized, into two categories: vertical and horizontal. These two categories are of a linear kind. This basic concept can be applied to various kinds of personal relations. For example, the parent-child relation is vertical, the sibling relation is horizontal; the superior-inferior relation is vertical, as opposed to the horizontal colleague relation. Both are important primary factors in relationships and constitute the core of a group's structure. It can be seen that, depending on the society, one has at times a more important function than the other and at times the two factors function equally.

If we postulate a social group embracing members with varoius [sic] different attributes, the method of tying together the constituent members will be based on the vertical relation. In other words vertical systems would link A and B who are different in quality. In contrast, a horizontal tie would be established between X and Y, who are of the same quality. When individuals having a certain attribute in common form a group the horizontal relationship functions by reason of this common quality. Theoretically, the horizontal tie between those of the same stratum functions in the development of caste and class, while the vertical tie functions in forming the cluster within which the upper-lower hierarchical order becomes more pronounced.

Let me illustrate these contrasting modes of social configuration with a simple example. A man is employed in a particular occupation and is also a member of a village community. In theory he belongs to two kinds of groups: the one, of his occupation (attribute) and the other of the village (frame). When the function of the former is the stronger an effective occupational group is formed which cuts across several villages; thus there is formed a distinct horizontal stratum which renders proportionally weaker the degree of coherence of the village community. By contrast, where the coherence of the village community is unusually strong, the links between members of the occupational group are weakened and, in extreme cases, the village unit may create deep divisions among members of the occupational group. This is a prominent and persistent tendency in Japanese society, representing a social configuration contrasting with that of Hindu caste society. For Japanese peasants, a village (local group) has been always the distinct group to which their primary membership was attached. In the Middle Ages when a large Buddhist temple formed a functional community embracing people of various occupations besides peasants belonging to its estate, it functioned as a kind of self-sufficient group, in which each occupational group was accommodated without functional linkage with any similar group outside the community. For example, carpenters of X temple rarely moved to another temple community and the situation was exactly similar to an occupational group in a modern institution. Throughout Japanese history, occupational groups, such as a guild, cross-cutting various local groups and institutions have been much less developed in comparison with those of China, India and the west. It should be also remembered that a trade union in Japan is always formed primarily by the institution, such as a company, and includes members of various kinds of qualifications and specialities, such as factory workers, office clerks and engineers.

In such a society a functional group consists always of heterogeneous elements, and the principle by which these elements are linked is always dominated by the vertical order. Certainly, in both kinds of social configuration, there exists a hierarchical order in the alignment of various groups. But when each occupational group is formed in such a way as to cut across various institutions it comes to possess an autonomy and strength which enable it to compete with other groups. In such a situation it is important that the ideology of the division of labour be sufficiently developed to counteract or balance the hierarchical ideology. However, when an occupational group of only small numbers exists within an institutional group, its members isolated from their fellows in other groups, there is a tendency for the hierarchical order to dominate the group and for the autonomy of the occupational group to diminish; the small, isolated segments become subject to the workings of the institutional group of which they form part. The result is the emergence of the vertical order in group organization.

The vertical relation which we predicted in theory from the ideals of social group formation in Japan becomes the actuating principle in creating cohesion among group members. Because of the overwhelming ascendancy of this vertical orientation, even a set of individuals sharing identical qualifications tends to create a difference among these individuals. As this is reinforced, an amazingly delicate and intricate system of ranking takes shape.

There are numerous examples of this ranking process. Among lathe operators with the same qualifications there exist differences of rank based on relative age, year of entry into the company or length of continuous service; among professors at the same college, rank can be assessed by the formal date of appointment; among commissioned officers in the former Japanese army the differences between ranks were very great, and it is said that even among second lieutenants distinct ranking was made on the basis of order of appointment. Among diplomats, there is a very wide gulf between first secretary and second secretary; within each grade there are informal ranks of senior and junior according to the year when the foreign service examination was passed.

This ranking-consciousness is not limited merely to official groups but is to be found also among writers and actors, that is, groups which are supposed to be engaged in work based on individual ability and should not therefore be bound by any institutional system. A well-known novelist, on being given one of the annual literary prizes, said, 'It is indeed a great honour for me. I am rather embarrassed to receive the award while some of my sempai (predecessors or elders) have not yet got it.' Sempai meant for him those whose careers began and who achieved fame and popularity some time before he himself achieved them. Another example of the same sort is to be found in the statement made by an actress who had had great success in a film. On account of this success, she demanded that her company increase her guaranteed payment: 'I would like my present guaranteed payment (Y500,000) to be doubled. I think I am entitled to it, because actress Y is getting more than Y1,000,000 in spite of her being kōhai (junior: having started her career later) and younger than I. I have been an actress in this company for more than eight years now, you know.' For the Japanese the established ranking order (based on duration of service within the same group and on age, rather than on individual ability) is overwhelmingly important in fixing the social order and measuring individual social values.

A Japanese finds his world clearly divided into three categories, sempai (seniors), kōhai (juniors) and dōryō. Dōryō, meaning 'one's colleagues', refers only to those with the same rank, not to all who do the same type of work in the same office or on the same shop floor; even among dōryō, differences in age, year of entry or of graduation from school or college contribute to a sense of sempai and kōhai. These three categories would be subsumed under the single term 'colleagues' in other societies.

This categorization is demonstrated in the three methods of addressing a second or third person; for example, Mr Tanaka may be addressed as Tanaka-san, Tanaka-kun Or Tanaka (i.e. without suffix). San is used for sempai, kun for kōhai and the name without suffix is reserved for dōryō.[6] The last form is comparable with the English usage of addressing by the Christian name.[7] But the use of this form is carefully restricted to those who are vey close to oneself. Even among dōryō, san is used towards those with whom one is not sufficiently familiar, while kun is used between those closer than those addressed by san, former class-mates, for example. A relationship which permits of address by surname only is of a specifically familiar nature, not unlike the French usage of tu. Therefore, a man may also address very intimate kōhai in this way, but these kōhai will use the san form of address to him. In the case of professionals, within thiS pattern, a sempai is addressed as sensei instead of san, sensei being the higher honorific term, used of teachers by their students, and also of profesionals by the general public.

It is important to note that this usage of terms of address, once determined by relationships in the earlier stages of a man's life or career, remains unchanged for the rest of his life. Let us imagine, for example, the case of X, once a student of Y, who, fifteen years afterwards, becomes a professor in the same department as Y and thus acquires equal status. X still addresses Y as sensei and will not refer to him as dōryō (colleague) to a third person. Y may address X as kun, treating him, that is, as kōhai, even in front of X's students or outsiders: Y has to be most broad-minded and sociable to address X as sensei in such a context (i.e. the English usage of Dr or Professor).

It may also be that when X is well known, but Y is not, Y may intentionally address X as kun in public in order to indicate that 'he is superior to X, X is only his kōhai'. It is the general tendency to indicate one's relatively higher status; this practice derives from the fact that the ranking order is perceived as ego-centred. Once established, vertical ranking functions as the charter of the social order, so that whatever the change in an individual's status, popularity or fame, there is a deeply ingrained reluctance to ignore or change the established order.

The relative rankings are thus centred on ego and everyone is placed in a relative locus within the firmly established vertical system. Such a system works against the formation of distinct strata within a group, which, even if it consists of homogeneous members in terms of qualification, tends to be organized according to hierarchical order. In this kind of society ranking becomes far more important than any differences in the nature of the work, or of status group. Even among those with the same training, qualifications or status, differences based on rank are always perceptible, and because the individuals concerned are deeply aware of the existence of such distinctions, these tend to overshadow and obscure even differences of occupation, status or class.

The precedence of elder over younger (chō-yō-no-jo) reflects the well-known moral ethic which was imported from China at a comparatively early stage in Japan's history. However, the Japanese application of this concept in actual life seems to have been somewhat different from that of the Chinese. An interesting example illustrates this discrepancy. When six Chinese shōgi (chess) players came to Japan recently to play against the Japanese, one thing that struck Japanese observers was the ranking order of the six players. In the account of their arrival carried by Asahishimbun, one of the leading Japanese daily newspapers, it was reported that Mr Wan, aged 17, the youngest of the six, stood fourth in order at the welcoming ceremony at Haneda Airport, and again at the reception party in Tokyo. The reporter went on to observe,

If we regard them according to the Japanese way of according precedence, Mr Wan, who is the youngest of them all and holds only nidan (second rank), should occupy the last seat in place of Mr Tsen, who though the eldest in years now takes the lowest place. They, however, take as the basis for position the order which resulted from the last title-match standings.

The Chinese are not always as conscious of order (seniority and rank, that is) as are the Japanese; they limit the effectiveness of seniority or rank to certain activities or situations and eliminate it from others. From what I have been able to observe, although the Chinese always appreciate manners which show respect towards those in a senior position, senior and junior might well stand on an equal footing in certain circumstances. The Chinese are able to readjust the order, or work according to a ranking established by a different criterion, by merit, for example, if the latter suits the circumstances.

In Japan once rank is established on the basis of seniority, it is applied to all circumstances, and to a great extent controls social life and individual activity. Seniority and merit are the principal criteria for the establishment of a social order; every society employs these criteria, although the weight given to each may differ according to social circumstances. In the west merit is given considerable importance, while in Japan the balance goes the other way. In other words, in Japan, in contrast to other societies, the provisions for recognition of merit are weak, and institutionalization of the social order has been effected largely by means of seniority; this is the more obvious criterion, assuming an equal ability in individuals entering the same kind of service.

The system of ranking by seniority is a simpler and more stable mechanism than the merit system, since, once it is set, it works automatically without need of any form of regulation or check. But at the same time this system brings with it a high degree of rigidity. There is only one ranking order for a given set of persons, regardless of variety of situation. No individual members of this set (not even the man who ranks highest) can make even a partial change. The only means of effecting change is by some drastic event which affects the principle of the order, or by the disintegration of the group.

It is because of this rigidity and stability that are produced by ranking that the latter functions as the principal controlling factor of social relations in Japan. The basic orientation of the social order permeates every aspect of society, far beyond the limits of the institutionalized group. This ranking order, in effect, regulates Japanese life.

In everyday affairs a man who has no awareness of relative rank is not able to speak or even sit and eat. When speaking, he is expected always to be ready with differentiated, delicate degrees of honorific expressions appropriate to the rank order between himself and the person he addresses. The expressions and the manner appropriate to a superior are never to be used to an inferior. Even among colleagues, it is only possible to dispense with honorifics when both parties are very intimate friends. In such contexts the English language is inadequate to supply appropriate equivalents. Behaviour and language are intimately interwoven in Japan.

The ranking order within a given institution affects not only the members of that institution but through them it affects the establishment of relations between persons from different institutions when they meet for the first time. On such occasions the first thing that the Japanese do is exchange name cards. This act has crucial social implications. Not only do name cards give information about the name (and the characters with which it is written) and the address; their more important function is to make clear the title, the position and the institution of the person who dispenses them. It is considered proper etiquette for a man to read carefully what is printed on the card, and to adjust his behavior, mode of address and so on in accordance with the information it gives him. By exchanging cards, both parties can gauge the relationship between them in terms of relative rank, locating each other within the known order of their society.[8] Only after this is done are they able to speak with assurance, since, before they can do so, they must be sure of the degree of honorific content and politeness they must put into their words.

In the west there are also certain codes which differentiate appropriate behaviour according to the nature of the relation between the speaker and the second person. But in Japan the range of differentiation is much wider and more elaborate, and delicate codification is necessary to meet each context and situation. I was asked one day by a French journalist who had just arrived in Tokyo to explain why a man changes his manner, depending upon the person he is addressing, to such a degree that the listener can hardly believe him to be the same speaker. This Frenchman had observed that even the voice changes (which could well be true, since he had no knowledge of Japanese and so was unable to notice the use of differentiating honorific words; he sensed the difference only from variations in sound).

Certainly there are personal differences in the degree to which people observe the rules of propriety, and there are also differences related to the varying situations in which they are in- volved, with the result that the examples I have quoted may be felt to be rather extreme. Some flaunt their higher status by haughtiness towards inferiors and excessive modesty towards superiors; others may prefer to conceal haughtiness, remaining modest even towards inferiors, a manner which is appreciated by the latter and may result in greater benefit to the superior. And some are simply less conscious of the order of rank, although these would probably account for only a rather small percentage.

But whatever the variations in individual behaviour, awareness of rank is deeply rooted in Japanese social behaviour. In describing an individual's personality, a Japanese will normally derive his objective criteria from a number of social patterns currently established. Institutional position and title constitute one of the major criteria, while a man's individual qualities tend to be overlooked.

Without consciousness of ranking, life could not be carried on smoothly in Japan, for rank is the social norm on which Japanese life is based. In a traditional Japanese house the arrangement of a room manifests this gradation of rank and clearly prescribes the ranking differences which are to be observed by those who use it. The highest seat is always at the centre backed by the tokonoma (alcove), where a painted scroll is hung and flowers are arranged; the lowest seat is nearest the entrance to the room. This arrangement never allows two or more individuals to be placed as equals. Whatever the nature of the gathering, those present will eventually establish a satisfactory order among themselves, after each of them has shown the necessary preliminaries of the etiquette of self-effacement. Status, age, popularity, sex, etc., are elements which contribute to the fixing of the order, but status is without exception the dominant factor.[9] A guest is always placed higher than the host unless his status is much lower than that of the host. A guest coming from a more distant place is accorded particularly respectful treatment.

There is no situation as awkward in Japan as when the appropriate order is ignored or broken ― when, for example, an inferior sits at a seat higher than that of his superior. It is often agreed that, in these 'modern' days, the younger generation tends to infringe the rules of order. But it is interesting to note that young people soon begin to follow the traditional order once they are employed, as they gradually realize the social cost that such infringement involves. The young Japanese, moreover, is never free of the seniority system. In schools there is a very distinct senior-junior ranking among students, which is observed particularly strictly among those who form sports clubs. In a student mountaineering club, for example, it is the students of a junior class who carry a heavier load while climbing, pitch the tent and prepare the evening meal under the surveillance of the senior students, who may sit smoking. When the preparations are over it is the senior students who take the meal first, served by the junior students. This strong rank consciousness, it is said, clearly reflects the practices of the former Japanese army.

In the West the use of a regulated table plan is restricted usually to occasions such as a formal dinner party, when the chief guest is placed at the right of the host and so on. But in Japan even at the supper table of a humble family there is no escape from the formality demanded by rank. At the start of the meal everyone should be served cooked rice by the mistress of the household. The bowls should be served in order of rank, from higher to lower: among family members, for example, the head of the household will be served first, followed by his nominal successor (his son or adopted son-in-law), other sons and daughters according to sex and seniority. Last of all come the mistress of the household and the wife of the successor. The sequence of serving thus clearly reflects the structure of the group.

Since ranking order appears so regularly in such essential aspects of daily life, the Japanese cannot help but be made extremely conscious of it. In fact, this consciousness is so strong that official rank is easily extended into private life. A superior in one's place of work is always one's superior wherever he is met, at a restaurant, at home, in the street. When wives meet, they, too, will behave towards each other in accordance with the ranks of their husbands, using honorific expressions and gestures appropriate to the established relationship between their husbands. A leader in Japan tends to display his leadership in any and every circumstance, even when leadership is in no way called for. American behaviour is quite different in this particular: my experience among Americans is that it is often very difficult to discover even who is the leader of a group (or who has the higher or lower status) except in circumstances which require that the leadership make itself known.